Friday, May 31, 2013

mealy macro on: macro model choice for policy makers

a story

"It is sometime in 2005/6. Consumption is very strong, and savings are low, and asset prices are high. You have good reason to think asset prices may be following a bubble. Your DSGE model has a consumption function based on an Euler equation, in which asset prices do not appear. It says a bursting house price bubble will have minimal effect. You ask your DSGE modellers if they are sure about this, and they admit they are not, and promise to come back in three years time with a model incorporating collateral effects. Your SEM modeller has a quick look at the data, and says there does seem to be some link between house prices and consumption, and promises to adjust the model equation and redo the forecast within a week. Now choose as a policy maker which type of model you would rather rely on."

more firm based modeling of cross border trade

" The size of the welfare gains from trade and the mechanisms through which these occur are central to policy debates about trade liberalisation. These include both multilateral trade negotiations such as the WTO Doha Round and regional integration decisions such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Over the last 20 years, trade economists have uncovered heterogeneous firm-level responses to trade liberalisation, which in turn inspired the development of new theories of international trade."

Blah

"Evidence of these heterogeneous firm-level responses comes from numerous empirical studies of disaggregated (firm- or plant-level) datasets following Bernard and Jensen (1995):

•A minority of firms participate in international markets, whether through exports, imports or multinational activity. Often 10% of a nation’s firms account for over 80% of all exports.

•These firms are larger, more productive, more capital intensive, more skill intensive and pay higher wages than domestic firms within the same industry.

•While most firms that trade supply few products to a handful of destination markets, a small number of traders account for the vast majority of the value of exports and imports.

Trade liberalisation reforms are found to induce intra-industry reallocations of resources, as low productivity firms exit and more productive firms expand to serve export markets. In turn, these reallocations towards more productive firms generate an increase in average industry productivity."

"A new survey of the new new trade theory

In our recent handbook chapter, we review the theories developed to capture these features of the data (Melitz and Redding 2013a). The basic elements of these models are simple:

•New entrants in an industry face uncertainty about their future productivity (or product quality appeal).

•Productivity/quality is revealed after a sunk entry cost is incurred.

•At this point, some firms realise that they cannot earn positive operating profits and exit the industry.

•The remaining firms continue to produce and those with high productivity or quality attain larger market shares and earn higher profits.

•The firms that select into exporting as well as selling locally are naturally the most productive since exporting involves additional costs.

When trade costs fall, export profits rise and a new logic leads to changes that raise average industry productivity:

•Some new firms become exporters (the most productive among those that did not previously export), while existing exporters increase their export sales (and hence their overall production levels).

•The higher export profits also induce additional entry into the domestic industry (as the returns to high productivity/quality increase).

•Non-exporters lose market share because of both increased import competition and the additional entry and hence shrink.

•This forces some of the least productive firms to exit, while some more productive firms expand.

These within-industry reallocations in response to trade liberalisation generate higher industry productivity – and represent a new potential source of gains from trade.

Do these heterogeneous firm responses matter for aggregate welfare?

While these new theories of heterogeneous firms in differentiated product markets have been extremely successful in accounting for features of disaggregated trade data, Arkolakis, Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2012) ask whether these new insights for micro-level data have altered our understanding of the aggregate welfare gains from trade.

They show that there exists a class of trade models (with and without firm-level differences across producers) in which a country’s domestic trade share (expenditure on its own goods relative to GDP) and the elasticity of trade with respect to trade costs (the percentage increase in trade from a 1% decrease in trade cost) are sufficient statistics for the aggregate welfare gains from trade. Under these circumstances, calculating the welfare gains from trade does not require knowledge of disaggregated features of international trade data. All one requires is aggregate data on trade shares and the trade elasticity (the sensitivity of aggregate trade to changes in trade costs). If two different models within this class are calibrated to deliver the same trade share and trade elasticity, then they also deliver the same welfare gains from trade – regardless of their different implications for the firm-level responses to trade.

Based on this result, the authors summarise the contribution of new theories of heterogeneous firms to our understanding of the aggregate welfare implications of trade as “So far, not much.”

A new source of gains from trade

In Melitz and Redding (2013b), we show that firm-level responses to trade that generate higher productivity do in fact represent a new source of gains from trade.

•We start with a model with heterogeneous firms, then compare it to a variant where we eliminate firm differences in productivity while keeping overall industry productivity constant.

We also keep all other model parameters (such as those governing trade costs and demand conditions) constant.

•This 'straw man' model has no reallocations across firms as a result of trade and hence features no productivity response to trade.

Yet it is constructed so as to deliver the same welfare prior to trade liberalisation. We then show that, for any given reduction in trade costs, the model with firm heterogeneity generates higher aggregate welfare gains from trade because it features an additional adjustment margin (the productivity response to trade via reallocations). We also show that these differences are quantitatively substantial, representing up to a few percentage points of GDP. We thus conclude that firm-level responses to trade and the associated productivity changes have important consequences for the aggregate welfare gains from trade.

Reconciling these findings

How can these findings be reconciled with the results obtained by Arkolakis, Costinot, and Rodriguez-Clare (2012)? Their approach compares models that are calibrated to deliver the same domestic trade share and trade elasticity (the sensitivity of aggregate trade to changes in trade costs). In so doing, this approach implicitly makes different assumptions about demand and trade costs conditions across the models that are under comparison (Simonovska and Waugh 2012). By assuming different levels of product differentiation across the models, and assuming different levels of trade costs, it is possible to have the different models predict the same gains from trade – even though they feature different firm-level responses. In contrast, our approach keeps all these 'structural' demand and cost conditions constant, and changes only the degree of firm heterogeneity (Melitz and Redding 2013b). This leads to different predictions for the welfare gains from trade.

One potential criticism of our approach is that one can estimate the trade elasticity (the sensitivity of aggregate trade to changes in trade costs) using aggregate trade data only – without requiring any specific assumptions about the firm-level responses to trade. Whatever assumptions are made about those firm-level responses (and the demand and trade-cost conditions), they should then be constructed so as to match that estimated aggregate elasticity. However, recent empirical work has shown that those underlying assumptions radically affect the measurement of the aggregate trade elasticity, and that this trade elasticity varies widely across sectors, countries, and the nature of the change in trade costs (see for example Helpman et al. 2008, Ossa 2012, and Simonovska and Waugh 2012). There is thus no single empirical trade-elasticity parameter that can be held constant across those different models.

Given the lack of a touchstone set of elasticities, we favour our approach to measuring the gains from trade arising from different models; one that maintains the same assumptions about demand and trade costs conditions across those models.

References

Arkolakis, C, A Costinot and A Rodriguez-Clare (2012) “New Trade Models, Same Old Gains,” The American Economic Review, 102(1), 94-130.

Bernard, A and J Bradford Jensen (1995) “Exporters, Jobs, and Wages in US Manufacturing: 1976-87,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics, 67-112.

Helpman, E, Melitz, M and Y Rubinstein (2008) “Estimating Trade Flows: Trading Partners and Trading Volumes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 441-87.

Melitz, M and S Redding (2013a) “Heterogeneous Firms and Trade,” Handbook of International Economics, Volume 4, Elsevier: North Holland, forthcoming, 2013. NBER Working Paper, 18652.

Melitz, M and S Redding (2013b) “Firm Heterogeneity and Aggregate Welfare,” NBER Working Paper, 18919.

Ossa, Ralph (2012) “Why Trade Matters After All,” NBER Working Paper, 18113.

Simonovska, I and M Waugh (2012) “Different Trade Models, Different Trade Elasticities,” New York University, mimeograph.

Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on emailShare on printMore Sharing Services54

LTV deprived Delong faces a future flooded with robots without the withering away of " the delicate machine " that is the market place

"To create wealth, you need ideas about how to shape matter and energy, additional energy itself to carry out the shaping, and instrumentalities to control the shaping as it is accomplished. The Industrial Revolution brought ideas and energy to the table, but human brains remained the only effective instrumentalities of control. As ideas and energy became cheap, the human brains that were their complements became valuable."

"But"

" as we move into a future of artificial intelligence that and into a future of biotechnology that grows itself as biological systems do, won’t human brains cease to be the only valuable instrumentalities of control?"

"It is not necessarily the case that “unskilled” workers’ standards of living will fall in absolute terms: the same factors that make human brains less valuable may well be working equally effectively to reduce the costs of life’s necessities, conveniences, and luxuries."

" But"

" wealth is likely to flow to the owners of productive – or perhaps fashionable – ideas,"

" and to owners of things that can be imitated only with great difficulty and high cost even with

dirt-cheap instrumentalities of control, dirt-cheap energy, and plentiful ideas."

"The lesson is clear"

"the marketplace is not guaranteed by nature to produce a long-run future characterized by

a reasonable degree of wealth inequality and relative poverty."

" Unless and until we recognize this fully"

" we will remain at the mercy of Keynes’s poorly understood “delicate machine.”

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

Parrot modeling

Model Imitation of market dynamics:

The collection of bare data streams

From a few selected metrics from an economy

Similarly

" generated " by a mechanism. http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr618.pdf

Monday, May 27, 2013

Rogoff invoked the non linear rate response path

Street name:

The sudden spike

And where is the fed in all this Kenny ?

The image of an overwhelmed CB is a joke

The CB runs it's own currency market if and when it chooses to

Whatrevents the fed from buying up entire issues

Err

Other then the fed itself

The only think we have to fear is the fed itself !

Fiscal injections scotched by fed

Yes the fed can constrict Net credit flows

To counter fiscal thrust funded with borrowed money

But how can you set up a test of pure fiscal activism ?

What is the neutral policy the fed must take ?

The hicks model tells us nothing if the fiscal borrowing doesn't move the nominal rate off the floor

Or even if it does but that change leaves corporate and household spending " unimpacted"

And the dollar doesn't strengthen or export buyers spending is " unaffected"

by the forex change

Saturday, May 25, 2013

How does Aggregate "supply constraint " reduce system wide dynamic efficiency improvements ?

Maybe

I don't get it ...

You still have opportunity to increase your gain

By innovation process or product

or re purposing or switching sectors

Even if now

you operate entirely in the black

Maybe reducing the power of the credit system

to guide over all investment flows from the commanding heights

Increases co ordination

If the system is set to operate in aggregate

in the red

Survival in aggregate requires credit infusions

Sunday, May 19, 2013

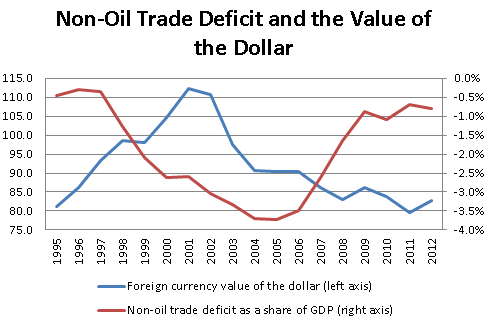

forex trade balance interaction

| ||||||||||||||

PK narrates the spiraling 70's and lo and behold no colander MAP no pigou inflation tax

when the spiral of output prices driven by wages chasing COL

and profits maintaining margins ..got insufferable

the answer to "the spiral" was at hand

weintraub or lerner :

a pigou tax or a warrant market

but

instead we got Volcker

"In elite mythology, the origins of the crisis of the 70s, like the supposed origins of our current crisis, lay in excess: too much debt, too much coddling of those slovenly proles via a strong welfare state. The suffering of 1979-82 was necessary payback."

"None of that is remotely true."

well that's a relief eh comrades!

"There was no deficit problem: government debt was low and stable or falling as a share of GDP during the 70s. "

"Rising welfare rolls may have been a big political problem, but a runaway welfare state more broadly just wasn’t an issue — hey, these days right-wingers complaining about a nation of takers tend to use the low-dependency 70s as a baseline. "

okay nouigh spoonheading :

"What we did have was a wage-price spiral:"

" workers demanding large wage increases (those were the days when workers actually could make demands) because they expected lots of inflation, firms raising prices because of rising costs, all exacerbated by big oil shocks. It was mainly a case of self-fulfilling expectations"

" the problem was to break the cycle."

"So why did we need a terrible recession? "

"...simply as a way to cool the action. "

"Someone — I’m pretty sure it was Martin Baily — described the inflation problem as being like what happens when everyone at a football game stands up to see the action better, and the result is that everyone is uncomfortable but nobody actually gets a better view."

come the double camel clutch submission hold

aka: the volckerdammerung

," stopping the game until everyone was seated again."

"this timeout destroyed millions of jobs and wasted trillions of dollars."

"Was there a better way? "

"Ideally, we should have been able to get all the relevant parties in a room and say, look, this inflation has to stop; you workers, reduce your wage demands, you businesses, cancel your price increases, and for our part, we agree to stop printing money so the whole thing is over. That way, you’d get price stability without the recession. "

" America wasn’t like that, and the decision was made to do it the hard, brutal way."

" This was not a policy triumph! It was, in a way, a confession of despair."

.

"60-year-old men should remember that a decade after the Volcker disinflation we were still very much in a national funk"

Saturday, May 18, 2013

Thursday, May 16, 2013

brad pugsley forgets NAIRU taboo line

he's thrashing smug uber rodent

micky kinkajou

" Kinsley claims that: "the lessons of Paul Volcker" are that "the Great Stagflation of the late 1970s" was caused by fiscal "Stimulus" which "is strong medicine--an addictive drug--and you don’t give the patient more than you absolutely have to."

a fairly common narrative actually

the usual line about the original sin

prior to the reagan eviction of the job class from the eden

of post war

"fairly strong job markets "

"Was he not alive in the late 1970s and early 1980s? "

asks bradkins

"Does he not remember that the large fiscal deficits of the 1970s and 1980s

came not during the Great Stagflation of the 1970s, but in the 1980s

after the Volcker Disinflation?"

its YOU dear brad that isn't singing here

from the dominant hymn book

at thomatose:

anne said...

micky kinkajou

" Kinsley claims that: "the lessons of Paul Volcker" are that "the Great Stagflation of the late 1970s" was caused by fiscal "Stimulus" which "is strong medicine--an addictive drug--and you don’t give the patient more than you absolutely have to."

a fairly common narrative actually

the usual line about the original sin

prior to the reagan eviction of the job class from the eden

of post war

"fairly strong job markets "

"Was he not alive in the late 1970s and early 1980s? "

asks bradkins

"Does he not remember that the large fiscal deficits of the 1970s and 1980s

came not during the Great Stagflation of the 1970s, but in the 1980s

after the Volcker Disinflation?"

its YOU dear brad that isn't singing here

from the dominant hymn book

at thomatose:

anne said...

anne said in reply to anne...

What Smith didn’t note, somewhat surprisingly, is that his argument is very close to Naomi Klein’s "Shock Doctrine," with its argument that elites systematically exploit disasters to push through neoliberal policies even if these policies are essentially irrelevant to the sources of disaster. I have to admit that I was predisposed to dislike Klein’s book when it came out, probably out of professional turf-defending and whatever — but her thesis really helps explain a lot about what’s going on in Europe in particular....

-- Paul Krugman

-- Paul Krugman

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to anne...

elites systematically exploit disasters to push through neoliberal policies even if these policies are essentially irrelevant to the sources of disaster.

[I would pare it down further. These (neoliberal) policies are the sources of disaster.]

[I would pare it down further. These (neoliberal) policies are the sources of disaster.]

Peter K. said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

Yeah but what are Naomi Klein's examples? Iraq? South America? They don't hold up. DeLong is right and Krugman is wrong here.

Klein's thesis is that the neoliberal elite intentionally blew the housing bubble and created the unregulated shadow banking system for the SOLE PURPOSE AND REASON of creating an epic financial crisis and deep downturn so that they would be able to cut Medicare and Social Security.

The elite aren't that smart or scheming.

Klein's thesis is that the neoliberal elite intentionally blew the housing bubble and created the unregulated shadow banking system for the SOLE PURPOSE AND REASON of creating an epic financial crisis and deep downturn so that they would be able to cut Medicare and Social Security.

The elite aren't that smart or scheming.

anne said in reply to Peter K....

Being profane and dealing in calumny is never right, as for South America we should find Naomi Klein repeatedly right as South America was historically turned to a United States corporate accessory.

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to Peter K....

The elite aren't that smart or scheming.

[Well they are not that smart anyway, but exploitive they have covered.]

[Well they are not that smart anyway, but exploitive they have covered.]

anne said in reply to anne...

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/04/hoisted-from-the-archives-tyler-cowen-thinks-naomi-klein-believes-her-own-bulls------grasping-reality-with-tractor-beams.html

April 8, 2010

Hoisted from the Archives: Tyler Cowen Thinks Naomi Klein Believes Her Own Bulls---

He reads her book. He doesn't think it meets minimum intellectual standards. I think he is right: now I can borrow Tyler's ideas and have an informed view.... *

"If nothing else, Ms. Klein's book provides an interesting litmus test as to who is willing to condemn its shoddy reasoning. In the New York Times, Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz defended the book: 'Klein is not an academic and cannot be judged as one.' So nonacademics get a pass on sloppy thinking, false 'facts,' and emotional appeals? In making economic claims, Ms. Klein demands to be judged by economists' standards — or at the very least, standards of simple truth or falsehood. Mr. Stiglitz continued: 'There are many places in her book where she oversimplifies. But Friedman and the other shock therapists were also guilty of oversimplification.' Have we come to citing the failures of one point of view to excuse the mistakes of another?"

* http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2007/10/tyler-cowen-thi.html

October 4, 2007

-- Brad DeLong

April 8, 2010

Hoisted from the Archives: Tyler Cowen Thinks Naomi Klein Believes Her Own Bulls---

He reads her book. He doesn't think it meets minimum intellectual standards. I think he is right: now I can borrow Tyler's ideas and have an informed view.... *

"If nothing else, Ms. Klein's book provides an interesting litmus test as to who is willing to condemn its shoddy reasoning. In the New York Times, Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz defended the book: 'Klein is not an academic and cannot be judged as one.' So nonacademics get a pass on sloppy thinking, false 'facts,' and emotional appeals? In making economic claims, Ms. Klein demands to be judged by economists' standards — or at the very least, standards of simple truth or falsehood. Mr. Stiglitz continued: 'There are many places in her book where she oversimplifies. But Friedman and the other shock therapists were also guilty of oversimplification.' Have we come to citing the failures of one point of view to excuse the mistakes of another?"

* http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2007/10/tyler-cowen-thi.html

October 4, 2007

-- Brad DeLong

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to anne...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Bradford_DeLong

...DeLong is both a liberal in the modern American political sense and a free trade neo-liberal. He has cited Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Andrei Shleifer, Milton Friedman, and Lawrence Summers (with whom he has co-authored numerous papers) as the economists who have had the greatest influence on his views...

...DeLong is both a liberal in the modern American political sense and a free trade neo-liberal. He has cited Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Andrei Shleifer, Milton Friedman, and Lawrence Summers (with whom he has co-authored numerous papers) as the economists who have had the greatest influence on his views...

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

Where is Paine? You can never find a socialist when you need one :<)

anne said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

Paine has repeatedly suggested reading Michal Kalecki, beating Paul Krugman to the suggestion:

http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2010/kalecki220510.html

1942

Political Aspects of Full Employment

By Michal Kalecki

1. A solid majority of economists is now of the opinion that, even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme, provided there is in existence adequate plan to employ all existing labour power, and provided adequate supplies of necessary foreign raw-materials may be obtained in exchange for exports.

If the government undertakes public investment (e.g. builds schools, hospitals, and highways) or subsidizes mass consumption (by family allowances, reduction of indirect taxation, or subsidies to keep down the prices of necessities), and if, moreover, this expenditure is financed by borrowing and not by taxation (which could affect adversely private investment and consumption), the effective demand for goods and services may be increased up to a point where full employment is achieved. Such government expenditure increases employment, be it noted, not only directly but indirectly as well, since the higher incomes caused by it result in a secondary increase in demand for consumer and investment goods....

http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2010/kalecki220510.html

1942

Political Aspects of Full Employment

By Michal Kalecki

1. A solid majority of economists is now of the opinion that, even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme, provided there is in existence adequate plan to employ all existing labour power, and provided adequate supplies of necessary foreign raw-materials may be obtained in exchange for exports.

If the government undertakes public investment (e.g. builds schools, hospitals, and highways) or subsidizes mass consumption (by family allowances, reduction of indirect taxation, or subsidies to keep down the prices of necessities), and if, moreover, this expenditure is financed by borrowing and not by taxation (which could affect adversely private investment and consumption), the effective demand for goods and services may be increased up to a point where full employment is achieved. Such government expenditure increases employment, be it noted, not only directly but indirectly as well, since the higher incomes caused by it result in a secondary increase in demand for consumer and investment goods....

anne said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

Paine has repeatedly suggested reading Michal Kalecki, beating Paul Krugman to the suggestion:

1942

Political Aspects of Full Employment

By Michal Kalecki

1. A solid majority of economists is now of the opinion that, even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme, provided there is in existence adequate plan to employ all existing labour power, and provided adequate supplies of necessary foreign raw-materials may be obtained in exchange for exports.

If the government undertakes public investment (e.g. builds schools, hospitals, and highways) or subsidizes mass consumption (by family allowances, reduction of indirect taxation, or subsidies to keep down the prices of necessities), and if, moreover, this expenditure is financed by borrowing and not by taxation (which could affect adversely private investment and consumption), the effective demand for goods and services may be increased up to a point where full employment is achieved. Such government expenditure increases employment, be it noted, not only directly but indirectly as well, since the higher incomes caused by it result in a secondary increase in demand for consumer and investment goods....

1942

Political Aspects of Full Employment

By Michal Kalecki

1. A solid majority of economists is now of the opinion that, even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme, provided there is in existence adequate plan to employ all existing labour power, and provided adequate supplies of necessary foreign raw-materials may be obtained in exchange for exports.

If the government undertakes public investment (e.g. builds schools, hospitals, and highways) or subsidizes mass consumption (by family allowances, reduction of indirect taxation, or subsidies to keep down the prices of necessities), and if, moreover, this expenditure is financed by borrowing and not by taxation (which could affect adversely private investment and consumption), the effective demand for goods and services may be increased up to a point where full employment is achieved. Such government expenditure increases employment, be it noted, not only directly but indirectly as well, since the higher incomes caused by it result in a secondary increase in demand for consumer and investment goods....

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to anne...

Yeah, I have noticed and am with him on that and most things.

I have gadflied Paine on political framing and full disclosure of uncertainty and long term intentions of inflation policy, but not on employment policy itself. Now Abba Lerner is a leap that I have just not had the time to consider well, but it is also so far off from any politically reachable solution that there is no hurry. At first blush, Abba Lerner's funtional finance is highly appealing if only...

I have gadflied Paine on political framing and full disclosure of uncertainty and long term intentions of inflation policy, but not on employment policy itself. Now Abba Lerner is a leap that I have just not had the time to consider well, but it is also so far off from any politically reachable solution that there is no hurry. At first blush, Abba Lerner's funtional finance is highly appealing if only...

Peter K. said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

Who is the imitator who is sullying his good name and reputation?

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to Peter K....

Only Doc Thoma could answer that one.

I really did not find anything that told me that there is an imitator. The Mr Paine version used something closer to complete sentences, which he obviously tired of quickly. My guess is that he was attempting to appease Anne, but just found it too tiresome and switched to the Ghost. My take on it is that he has found a better use of his time in retirement and will not be blogging as much.

I really did not find anything that told me that there is an imitator. The Mr Paine version used something closer to complete sentences, which he obviously tired of quickly. My guess is that he was attempting to appease Anne, but just found it too tiresome and switched to the Ghost. My take on it is that he has found a better use of his time in retirement and will not be blogging as much.

i sully myself alas

ghosty paine

is a name for late emerging comments

retrieved from the spam trap by our host

ghosty paine

is a name for late emerging comments

retrieved from the spam trap by our host

anne said in reply to Darryl FKA Ron...

The problem is not in wearing any particular label, but in a need to savage, profanely savage in this instance, scholars or researchers who differ from any preconceived stance or slant adopted by the academic. That tends to prejudice the audience of the academic.

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to anne...

That tends to prejudice the audience of the academic.

[Not sure which audience that yor refer to. Class interest bias is already baked into the layer cake of elite thinking from the plutocrats to the oligarchs and even unto the sycophants. Among the vast majority of the electorate, then talking points are sorted out through confirmation bias of their ideological preferences to greater and lesser degrees. Open minded free thought is a rarity, but it has the clarity to see through such prejudicial rhetoric and nullify its effect.]

[Not sure which audience that yor refer to. Class interest bias is already baked into the layer cake of elite thinking from the plutocrats to the oligarchs and even unto the sycophants. Among the vast majority of the electorate, then talking points are sorted out through confirmation bias of their ideological preferences to greater and lesser degrees. Open minded free thought is a rarity, but it has the clarity to see through such prejudicial rhetoric and nullify its effect.]

anne said in reply to anne...

http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=07/08/15/1432250

August 15, 2007

Lost Worlds

By Naomi Klein

American Sociological Association

New York City

I think it matters that we had ideas all along, that there were always alternatives to the free market. And we need to retell our own history and understand that history, and we have to have all the shocks and all the losses, the loss of lives, in that story, because history didn't end. There were alternatives. They were chosen, and then they were stolen. They were stolen by military coups. They were stolen by massacres. They stolen by trickery, by deception. They were stolen by terror.

We who say we believe in this other world need to know that we are not losers. We did not lose the battle of ideas. We were not outsmarted, and we were not out-argued. We lost because we were crushed. Sometimes we were crushed by army tanks, and sometimes we were crushed by think tanks. And by think tanks, I mean the people who are paid to think by the makers of tanks. Now, most effective we have seen is when the army tanks and the think tanks team up. The quest to impose a single world market has casualties now in the millions, from Chile then to Iraq today. These blueprints for another world were crushed and disappeared because they are popular and because, when tried, they work. They're popular because they have the power to give millions of people lives with dignity, with the basics guaranteed. They are dangerous because they put real limits on the rich, who respond accordingly. Understanding this history, understanding that we never lost the battle of ideas, that we only lost a series of dirty wars, is key to building the confidence that we lack, to igniting the passionate intensity that we need....

August 15, 2007

Lost Worlds

By Naomi Klein

American Sociological Association

New York City

I think it matters that we had ideas all along, that there were always alternatives to the free market. And we need to retell our own history and understand that history, and we have to have all the shocks and all the losses, the loss of lives, in that story, because history didn't end. There were alternatives. They were chosen, and then they were stolen. They were stolen by military coups. They were stolen by massacres. They stolen by trickery, by deception. They were stolen by terror.

We who say we believe in this other world need to know that we are not losers. We did not lose the battle of ideas. We were not outsmarted, and we were not out-argued. We lost because we were crushed. Sometimes we were crushed by army tanks, and sometimes we were crushed by think tanks. And by think tanks, I mean the people who are paid to think by the makers of tanks. Now, most effective we have seen is when the army tanks and the think tanks team up. The quest to impose a single world market has casualties now in the millions, from Chile then to Iraq today. These blueprints for another world were crushed and disappeared because they are popular and because, when tried, they work. They're popular because they have the power to give millions of people lives with dignity, with the basics guaranteed. They are dangerous because they put real limits on the rich, who respond accordingly. Understanding this history, understanding that we never lost the battle of ideas, that we only lost a series of dirty wars, is key to building the confidence that we lack, to igniting the passionate intensity that we need....

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to anne...

Socialism is looking better all the time. Given the limited alternatives among Libertarian and reactionary conservatives, which are both covert if not overt neoliberals, along with liberals that are overt free trade neoliberals, then we have such a line-up of political choices that would put a wry smile on ol' Karl Marx's face.

paine said in reply to anne...

krugman on kalecki .....

master K

"....suggested that business interests hate Keynesian economics because they fear that it might work — and in so doing mean that politicians would no longer have to abase themselves before businessmen in the name of preserving confidence"

EXACTIMENTO !!!!!!

but some how after answering the question very concisely

pk chooses to go for the booby prize

"This is pretty close to the argument that we must have austerity, because stimulus might remove the incentive for structural reform "

????????????????????????

in fact perpetually tightr job markets

maimtaimed by fiscal policy

thru

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and pin

transfer-credit control system

nope pk goes dark side rudy meidner here

ie

the winnowing process only demand constrained market based production systems can

agitate firms

to continue innovating and renovating

by exfoliating loser outfits

yup

purge the rotten ness

maybe not with apocolyptic contractions and stags

but by a consistent demand scarcity

thru

macro managed

job and credit rationing

master K

"....suggested that business interests hate Keynesian economics because they fear that it might work — and in so doing mean that politicians would no longer have to abase themselves before businessmen in the name of preserving confidence"

EXACTIMENTO !!!!!!

but some how after answering the question very concisely

pk chooses to go for the booby prize

"This is pretty close to the argument that we must have austerity, because stimulus might remove the incentive for structural reform "

????????????????????????

in fact perpetually tightr job markets

maimtaimed by fiscal policy

thru

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and pin

transfer-credit control system

nope pk goes dark side rudy meidner here

ie

the winnowing process only demand constrained market based production systems can

agitate firms

to continue innovating and renovating

by exfoliating loser outfits

yup

purge the rotten ness

maybe not with apocolyptic contractions and stags

but by a consistent demand scarcity

thru

macro managed

job and credit rationing

missing section

in above

following

"in fact perpetually tightr job markets

maimtaimed(sic) by fiscal policy

thru

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and pin

transfer-credit control system "

read this:

i set up that in time would force a blow up

the existing

"autonomous firm pricing system"

replacing it with a huge sublation

where price change externalities are internalized

thru mark up warrant markets

crudly pre figured here:

by lerner-colander

http://books.google.com/books/about/MAP_a_market_anti_inflation_plan.html?id=nlkPAQAAMAAJ

in above

following

"in fact perpetually tightr job markets

maimtaimed(sic) by fiscal policy

thru

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and pin

transfer-credit control system "

read this:

i set up that in time would force a blow up

the existing

"autonomous firm pricing system"

replacing it with a huge sublation

where price change externalities are internalized

thru mark up warrant markets

crudly pre figured here:

by lerner-colander

http://books.google.com/books/about/MAP_a_market_anti_inflation_plan.html?id=nlkPAQAAMAAJ

anne said in reply to paine ...

in fact perpetually tighter job markets

maintained by fiscal policy

through

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and print

transfer-credit control system

set up that in time and it would force a blow up of

the existing

"autonomous firm pricing system"

replacing it with a huge sublation

where price change externalities are internalized

through mark up warrant markets

[ What is "sublation?"

I do not like iPads, which are awful for typing comments. ]

maintained by fiscal policy

through

the tax cut and borrow

monetize and print

transfer-credit control system

set up that in time and it would force a blow up of

the existing

"autonomous firm pricing system"

replacing it with a huge sublation

where price change externalities are internalized

through mark up warrant markets

[ What is "sublation?"

I do not like iPads, which are awful for typing comments. ]

anne said in reply to paine ...

After several readings, I do not understand the complaint. What am I missing?

rudy meidner ?

retain macro demand constraints

to control the wage price spiral and the innovation incentives

believed in corporate rent systems

and purging rotten ness

he just wanted most of the rents

taxed away and invested in

a national

"pension fund for all the people"

retain macro demand constraints

to control the wage price spiral and the innovation incentives

believed in corporate rent systems

and purging rotten ness

he just wanted most of the rents

taxed away and invested in

a national

"pension fund for all the people"

im1dc said...

ABC news is reporting

"Now Venezuela Is Running out of Toilet Paper"

By FABIOLA SANCHEZ and KARL RITTER

CARACAS, Venezuela... May 16, 2013... (AP)

"First milk, butter, coffee and cornmeal ran short. Now Venezuela is running out of the most basic of necessities — toilet paper.

Blaming political opponents for the shortfall, as it does for other shortages, the embattled socialist government says it will import 50 million rolls to boost supplies.

That was little comfort to consumers struggling to find toilet paper on Wednesday.

"This is the last straw," said Manuel Fagundes, a shopper hunting for tissue in downtown Caracas. "I'm 71 years old and this is the first time I've seen this."..."

========================================================

How embarrassing for the World Socialist Anti-America Haters.

"Now Venezuela Is Running out of Toilet Paper"

By FABIOLA SANCHEZ and KARL RITTER

CARACAS, Venezuela... May 16, 2013... (AP)

"First milk, butter, coffee and cornmeal ran short. Now Venezuela is running out of the most basic of necessities — toilet paper.

Blaming political opponents for the shortfall, as it does for other shortages, the embattled socialist government says it will import 50 million rolls to boost supplies.

That was little comfort to consumers struggling to find toilet paper on Wednesday.

"This is the last straw," said Manuel Fagundes, a shopper hunting for tissue in downtown Caracas. "I'm 71 years old and this is the first time I've seen this."..."

========================================================

How embarrassing for the World Socialist Anti-America Haters.

anne said...

How embarrassing for the World Socialist Anti-America Haters.

[ Notice the language of ceaseless slander, hatred and attempted intimidation. ]

[ Notice the language of ceaseless slander, hatred and attempted intimidation. ]

im1dc said in reply to anne...

If facts intimidate you then so be it.

BTW, we've had this discussion previously, it is not "slander" since slander is spoken, it would have to be libel since libel is written.

Yet, it is neither since it is truthful and fact based, the standard legal defense against both charges, proving them baseless, since the truth can't be slander or libel.

And, I don't hate Venezuela or Venezuelans. I only know one and she's a foxy, lively, and accomplished PT with world class taste in hand made silver jewelry from custom jewelers in her country. Can't hate that, gotta love and respect it.

BTW, we've had this discussion previously, it is not "slander" since slander is spoken, it would have to be libel since libel is written.

Yet, it is neither since it is truthful and fact based, the standard legal defense against both charges, proving them baseless, since the truth can't be slander or libel.

And, I don't hate Venezuela or Venezuelans. I only know one and she's a foxy, lively, and accomplished PT with world class taste in hand made silver jewelry from custom jewelers in her country. Can't hate that, gotta love and respect it.

im1dc said in reply to paine ...

Not so fast, wouldn't Venezuela be much better off if they turn to the Chinese Communist system of controlled capitalism and stopped expropriating from the producers?

It is OK to admire Castro and Hugo and the other Leftist Latin American leaders for the good they have done imo, but that isn't enough, one must also look at everything they have done and criticize their faults too, imo.

I'm thinking you probably begrudgingly agree.

It is OK to admire Castro and Hugo and the other Leftist Latin American leaders for the good they have done imo, but that isn't enough, one must also look at everything they have done and criticize their faults too, imo.

I'm thinking you probably begrudgingly agree.

paine said in reply to im1dc...

good response

we ought to exchange views on this

but too man of my comments are speared like fat ugly fish

by the site's spaminator x.0

we ought to exchange views on this

but too man of my comments are speared like fat ugly fish

by the site's spaminator x.0

anne said in reply to anne...

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/16/the-smithkleinkalecki-theory-of-austerity/

May 16, 2013

The Smith/Klein/Kalecki Theory of Austerity

By Paul Krugman

What Smith didn’t note, somewhat surprisingly, is that his argument is very close to Naomi Klein’s "Shock Doctrine," with its argument that elites systematically exploit disasters to push through neoliberal policies even if these policies are essentially irrelevant to the sources of disaster. I have to admit that I was predisposed to dislike Klein’s book when it came out, probably out of professional turf-defending and whatever — but her thesis really helps explain a lot about what’s going on in Europe in particular....

-- Paul Krugman

[ Naomi Klein was devastatingly right about Latin America, but remarkably economists dismissed the rightness as though political-economic movements from Guatemala or Honduras to Chile were not repeatedly designed for the sake of corporate and political interests in the United States. ]

May 16, 2013

The Smith/Klein/Kalecki Theory of Austerity

By Paul Krugman

What Smith didn’t note, somewhat surprisingly, is that his argument is very close to Naomi Klein’s "Shock Doctrine," with its argument that elites systematically exploit disasters to push through neoliberal policies even if these policies are essentially irrelevant to the sources of disaster. I have to admit that I was predisposed to dislike Klein’s book when it came out, probably out of professional turf-defending and whatever — but her thesis really helps explain a lot about what’s going on in Europe in particular....

-- Paul Krugman

[ Naomi Klein was devastatingly right about Latin America, but remarkably economists dismissed the rightness as though political-economic movements from Guatemala or Honduras to Chile were not repeatedly designed for the sake of corporate and political interests in the United States. ]

anne said...

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/16/the-sadomonetarists-of-basel/

May 16, 2013

The Sadomonetarists of Basel

By Paul Krugman

The Wall Street Journal highlights a speech by Jaime Caruana, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, warning of the dangers of easy money and the need to raise rates now to avert … something or other. And his views matter, says the Journal:

"Mr. Caruana is no disgruntled outvoted hawk on a policy-setting council, trying desperately to set the record straight after being outvoted. Rather, he’s the mouthpiece for a global college of central bankers, almost all of whom find themselves under intense pressure from their national governments to keep things ticking over while they try to repair the economy.

"His views also matter for another reason: the BIS is one of the few international financial institutions (some say the only one) to see the financial crisis coming and to issue clear warnings ahead of time."

I guess we can check the record here and see just how prescient the BIS was. What I do recall, however — which the Journal apparently doesn’t — is that the BIS has spent years warning about the dangers of low interest rates. Except that a couple of years back it was telling a completely different story about why we needed to raise rates; you see, the big danger was of imminent inflation:

" 'Global inflation pressures are rising rapidly as commodity prices soar and as the global recovery runs into capacity

May 16, 2013

The Sadomonetarists of Basel

By Paul Krugman

The Wall Street Journal highlights a speech by Jaime Caruana, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, warning of the dangers of easy money and the need to raise rates now to avert … something or other. And his views matter, says the Journal:

"Mr. Caruana is no disgruntled outvoted hawk on a policy-setting council, trying desperately to set the record straight after being outvoted. Rather, he’s the mouthpiece for a global college of central bankers, almost all of whom find themselves under intense pressure from their national governments to keep things ticking over while they try to repair the economy.

"His views also matter for another reason: the BIS is one of the few international financial institutions (some say the only one) to see the financial crisis coming and to issue clear warnings ahead of time."

I guess we can check the record here and see just how prescient the BIS was. What I do recall, however — which the Journal apparently doesn’t — is that the BIS has spent years warning about the dangers of low interest rates. Except that a couple of years back it was telling a completely different story about why we needed to raise rates; you see, the big danger was of imminent inflation:

" 'Global inflation pressures are rising rapidly as commodity prices soar and as the global recovery runs into capacity

paine said...

in the final analysis

pk blows the kalecki message

because he conceives of structural reforms entirely within the context of the present MNC sustaining system

implicitly he asks

"what will sustain and hopefully improve the present system'

hence his implicit observence of a NAIRU taboo line

debating whether that line is at 7 or 4 percent etc

is not the key

its the notion

to prevent

wage price spirals which are lethal

to the present system

we forgo higher output and employment

ie higher social mobilization for production

yes nairu as lethality

not

harbinger of the deeper structural "limitations"

of the present system

screaming at us

to sublate them

pk blows the kalecki message

because he conceives of structural reforms entirely within the context of the present MNC sustaining system

implicitly he asks

"what will sustain and hopefully improve the present system'

hence his implicit observence of a NAIRU taboo line

debating whether that line is at 7 or 4 percent etc

is not the key

its the notion

to prevent

wage price spirals which are lethal

to the present system

we forgo higher output and employment

ie higher social mobilization for production

yes nairu as lethality

not

harbinger of the deeper structural "limitations"

of the present system

screaming at us

to sublate them

anne said in reply to anne...

in the final analysis

PK blows the Kalecki message

because he conceives of structural reforms entirely within the context of the present multinational corporation sustaining system

implicitly he asks

"what will sustain and hopefully improve the present system?"

hence his implicit observance of a non-accelerating rate of unemployment taboo line

debating whether that line is at 7 or 4 percent etc

is not the key

it's the notion

to prevent

wage price spirals which are lethal

to the present system

we forgo higher output and employment

ie higher social mobilization for production

yes NAIRU as lethality

not

harbinger of the deeper structural "limitations"

of the present system

screaming at us

to sublate * them

* Assimilate

[ Really nice. ]

PK blows the Kalecki message

because he conceives of structural reforms entirely within the context of the present multinational corporation sustaining system

implicitly he asks

"what will sustain and hopefully improve the present system?"

hence his implicit observance of a non-accelerating rate of unemployment taboo line

debating whether that line is at 7 or 4 percent etc

is not the key

it's the notion

to prevent

wage price spirals which are lethal

to the present system

we forgo higher output and employment

ie higher social mobilization for production

yes NAIRU as lethality

not

harbinger of the deeper structural "limitations"

of the present system

screaming at us

to sublate * them

* Assimilate

[ Really nice. ]

paine said in reply to anne...

sublate

is one of the terms

used by us moth eaten old marxo-hegelians

we use it to label the "novel"

institutional arrangements

that emerge during the formation

of the "next stage "

of world historical social development

is one of the terms

used by us moth eaten old marxo-hegelians

we use it to label the "novel"

institutional arrangements

that emerge during the formation

of the "next stage "

of world historical social development

pk on master K

"Two and a half years ago Mike Konczal reminded us of a classic 1943 (!) essay by Michal Kalecki"

MASTER K sez pk

" .. suggested that business interests hate Keynesian economics because they fear that it might work — and in so doing mean that politicians would no longer have to abase themselves before businessmen in the name of preserving confidence"

yup so far so good

but comes a zoink

." This is pretty close to the argument that we must have austerity, because stimulus might remove the incentive for structural reform"

what ?

pk drives to the gates of enlightenment

reads the sign there and..

drives back to hooterville

and to add piffle on puffle

" that, ...., gives businesses the confidence they need before deigning to produce recovery."

MASTER K sez pk

" .. suggested that business interests hate Keynesian economics because they fear that it might work — and in so doing mean that politicians would no longer have to abase themselves before businessmen in the name of preserving confidence"

yup so far so good

but comes a zoink

." This is pretty close to the argument that we must have austerity, because stimulus might remove the incentive for structural reform"

what ?

pk drives to the gates of enlightenment

reads the sign there and..

drives back to hooterville

and to add piffle on puffle

" that, ...., gives businesses the confidence they need before deigning to produce recovery."

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

pk recaps the just so story of the oecd stag path avec notes by OP

in media res...

"....statistical techniques suddenly made a remarkable number of prominent people look foolish.

The real mystery, however, was why Reinhart-Rogoff was ever taken seriously, let alone canonized"

"So why wasn’t there more caution?"

" The answer, both politics and psychology: the case for austerity was and is one that many powerful people want to believe, leading them to seize on anything that looks like a justification."

the game is already lost

"So was a second Great Depression about to unfold?"

" The good news was that we had, or thought we had, several big advantages over our grandfathers"

,On the structural side, probably the biggest advantage over the 1930s was the way taxes and social insurance programs—both much bigger than they were in 1929—acted as “automatic stabilizers.” Wages might fall, but overall income didn’t fall in proportion, both because tax collections plunged and because government checks continued to flow for Social Security, Medicare, unemployment benefits, and more. In effect, the existence of the modern welfare state put a floor on total spending, and therefore prevented the economy’s downward spiral from going too far."

a chance to generalize this sub systems capacity

not just as off set and floor maker

but as rapid automatic "re mobilizer"

blasting aside pk's nod

to friedman disciple gentle ben

"economists had learned from John Maynard Keynes that under depression conditions government spending can be an effective way to create jobs."

AND

"They had learned from FDR’s disastrous turn toward austerity in 1937 that abandoning monetary and fiscal stimulus too soon can be a very big mistake."

back to ben

"the Federal Reserve not only slashed interest rates, but stepped into the markets to buy everything from commercial paper to long-term government debt"

now keynes

" the Obama administration pushed through an $800 billion program of tax cuts and spending increases"

.

"Now, some economists..... warned from the beginning that these monetary and fiscal actions, although welcome, were too small given the severity of the economic shock."

" Indeed, by the end of 2009 it was clear that although the situation had stabilized,

the economic crisis was deeper than policymakers had acknowledged, and likely to prove more persistent than they had imagined."

pk what if a oecd stag

a yellow flag on the "first world "track

was good for "our" corporate global system of profit arbitrage ?

nope

" one might have expected "

he sez

"a second round of stimulus to deal with the economic shortfall"

why ?

.

What actually happened, however, was a sudden reversal.

How decisive was the turn in policy? Figure 1, which is taken from the IMF’s most recent World Economic Outlook, shows how real government spending behaved in this crisis compared with previous recessions; in the figure, year zero is the year before global recession (2007 in the current slump), and spending is compared with its level in that base year. What you see is that the widespread belief that we are experiencing runaway government spending is false—on the contrary, after a brief surge in 2009, government spending began falling in both Europe and the United States, and is now well below its normal trend. The turn to austerity was very real, and quite large.

How decisive was the turn in policy? Figure 1, which is taken from the IMF’s most recent World Economic Outlook, shows how real government spending behaved in this crisis compared with previous recessions; in the figure, year zero is the year before global recession (2007 in the current slump), and spending is compared with its level in that base year. What you see is that the widespread belief that we are experiencing runaway government spending is false—on the contrary, after a brief surge in 2009, government spending began falling in both Europe and the United States, and is now well below its normal trend. The turn to austerity was very real, and quite large.

On the face of it, this was a very strange turn for policy to take. Standard textbook economics says that slashing government spending reduces overall demand, which leads in turn to reduced output and employment. This may be a desirable thing if the economy is overheating and inflation is rising; alternatively, the adverse effects of reduced government spending can be offset. Central banks (the Fed, the European Central Bank, or their counterparts elsewhere) can cut interest rates, inducing more private spending. However, neither of these conditions applied in early 2010, or for that matter apply now. The major advanced economies were and are deeply depressed, with no hint of inflationary pressure. Meanwhile, short-term interest rates, which are more or less under the central bank’s control, are near zero, leaving little room for monetary policy to offset reduced government spending. So Economics 101 would seem to say that all the austerity we’ve seen is very premature, that it should wait until the economy is stronger.

The question, then, is why economic leaders were so ready to throw the textbook out the window.

One answer is that many of them never believed in that textbook stuff in the first place. The German political and intellectual establishment has never had much use for Keynesian economics; neither has much of the Republican Party in the United States. In the heat of an acute economic crisis—as in the autumn of 2008 and the winter of 2009—these dissenting voices could to some extent be shouted down; but once things had calmed they began pushing back hard.

A larger answer is the one we’ll get to later: the underlying political and psychological reasons why many influential figures hate the notions of deficit spending and easy money. Again, once the crisis became less acute, there was more room to indulge in these sentiments.

In addition to these underlying factors, however, were two more contingent aspects of the situation in early 2010: the new crisis in Greece, and the appearance of seemingly rigorous, high-quality economic research that supported the austerian position.

If Greece provided the obvious real-world cautionary tale, Reinhart and Rogoff seemed to provide the math. Their paper seemed to show not just that debt hurts growth, but that there is a “threshold,” a sort of trigger point, when debt crosses 90 percent of GDP. Go beyond that point, their numbers suggested, and economic growth stalls. Greece, of course, already had debt greater than the magic number. More to the point, major advanced countries, the United States included, were running large budget deficits and closing in on the threshold. Put Greece and Reinhart-Rogoff together, and there seemed to be a compelling case for a sharp, immediate turn toward austerity.

But wouldn’t such a turn toward austerity in an economy still depressed by private deleveraging have an immediate negative impact? Not to worry, said another remarkably influential academic paper, “Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes Versus Spending,” by Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna.

One of the especially good things in Mark Blyth’s Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea is the way he traces the rise and fall of the idea of “expansionary austerity,” the proposition that cutting spending would actually lead to higher output. As he shows, this is very much a proposition associated with a group of Italian economists (whom he dubs “the Bocconi boys”) who made their case with a series of papers that grew more strident and less qualified over time, culminating in the 2009 analysis by Alesina and Ardagna.

In essence, Alesina and Ardagna made a full frontal assault on the Keynesian proposition that cutting spending in a weak economy produces further weakness. Like Reinhart and Rogoff, they marshaled historical evidence to make their case. According to Alesina and Ardagna, large spending cuts in advanced countries were, on average, followed by expansion rather than contraction. The reason, they suggested, was that decisive fiscal austerity created confidence in the private sector, and this increased confidence more than offset any direct drag from smaller government outlays.

As Mark Blyth documents, this idea spread like wildfire. Alesina and Ardagna made a special presentation in April 2010 to the Economic and Financial Affairs Council of the European Council of Ministers; the analysis quickly made its way into official pronouncements from the European Commission and the European Central Bank. Thus in June 2010 Jean-Claude Trichet, the then president of the ECB, dismissed concerns that austerity might hurt growth:

By the summer of 2010, then, a full-fledged austerity orthodoxy had taken shape, becoming dominant in European policy circles and influential on this side of the Atlantic. So how have things gone in the almost three years that have passed since?

The turn to austerity after 2010, however, was so drastic, particularly in European debtor nations, that the usual cautions lose most of their force. Greece imposed spending cuts and tax increases amounting to 15 percent of GDP; Ireland and Portugal rang in with around 6 percent; and unlike the half-hearted efforts at stimulus, these cuts were sustained and indeed intensified year after year. So how did austerity actually work?

The answer is that the results were disastrous—just about as one would have predicted from textbook macroeconomics. Figure 2, for example, shows what happened to a selection of European nations (each represented by a diamond-shaped symbol). The horizontal axis shows austerity measures—spending cuts and tax increases—as a share of GDP, as estimated by the International Monetary Fund. The vertical axis shows the actual percentage change in real GDP. As you can see, the countries forced into severe austerity experienced very severe downturns, and the downturns were more or less proportional to the degree of austerity.

The answer is that the results were disastrous—just about as one would have predicted from textbook macroeconomics. Figure 2, for example, shows what happened to a selection of European nations (each represented by a diamond-shaped symbol). The horizontal axis shows austerity measures—spending cuts and tax increases—as a share of GDP, as estimated by the International Monetary Fund. The vertical axis shows the actual percentage change in real GDP. As you can see, the countries forced into severe austerity experienced very severe downturns, and the downturns were more or less proportional to the degree of austerity.

There have been some attempts to explain away these results, notably at the European Commission. But the IMF, looking hard at the data, has not only concluded that austerity has had major adverse economic effects, it has issued what amounts to a mea culpa for having underestimated these adverse effects.*

But is there any alternative to austerity? What about the risks of excessive debt?

In early 2010, with the Greek disaster fresh in everyone’s mind, the risks of excessive debt seemed obvious; those risks seemed even greater by 2011, as Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Italy joined the ranks of nations having to pay large interest rate premiums. But a funny thing happened to other countries with high debt levels, including Japan, the United States, and Britain: despite large deficits and rapidly rising debt, their borrowing costs remained very low. The crucial difference, as the Belgian economist Paul DeGrauwe pointed out, seemed to be whether countries had their own currencies, and borrowed in those currencies. Such countries can’t run out of money because they can print it if needed, and absent the risk of a cash squeeze, advanced nations are evidently able to carry quite high levels of debt without crisis.

Three years after the turn to austerity, then, both the hopes and the fears of the austerians appear to have been misplaced. Austerity did not lead to a surge in confidence; deficits did not lead to crisis. But wasn’t the austerity movement grounded in serious economic research? Actually, it turned out that it wasn’t—the research the austerians cited was deeply flawed.

First to go down was the notion of expansionary austerity. Even before the results of Europe’s austerity experiment were in, the Alesina-Ardagna paper was falling apart under scrutiny. Researchers at the Roosevelt Institute pointed out that none of the alleged examples of austerity leading to expansion of the economy actually took place in the midst of an economic slump; researchers at the IMF found that the Alesina-Ardagna measure of fiscal policy bore little relationship to actual policy changes. “By the middle of 2011,” Blyth writes, “empirical and theoretical support for expansionary austerity was slipping away.” Slowly, with little fanfare, the whole notion that austerity might actually boost economies slunk off the public stage.

Reinhart-Rogoff lasted longer, even though serious questions about their work were raised early on. As early as July 2010 Josh Bivens and John Irons of the Economic Policy Institute had identified both a clear mistake—a misinterpretation of US data immediately after World War II—and a severe conceptual problem. Reinhart and Rogoff, as they pointed out, offered no evidence that the correlation ran from high debt to low growth rather than the other way around, and other evidence suggested that the latter was more likely. But such criticisms had little impact; for austerians, one might say, Reinhart-Rogoff was a story too good to check.

So the revelations in April 2013 of the errors of Reinhart and Rogoff came as a shock. Despite their paper’s influence, Reinhart and Rogoff had not made their data widely available—and researchers working with seemingly comparable data hadn’t been able to reproduce their results. Finally, they made their spreadsheet available to Thomas Herndon, a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst—and he found it very odd indeed. There was one actual coding error, although that made only a small contribution to their conclusions. More important, their data set failed to include the experience of several Allied nations—Canada, New Zealand, and Australia—that emerged from World War II with high debt but nonetheless posted solid growth. And they had used an odd weighting scheme in which each “episode” of high debt counted the same, whether it occurred during one year of bad growth or seventeen years of good growth.

Without these errors and oddities, there was still a negative correlation between debt and growth—but this could be, and probably was, mostly a matter of low growth leading to high debt, not the other way around. And the “threshold” at 90 percent vanished, undermining the scare stories being used to sell austerity.

Not surprisingly, Reinhart and Rogoff have tried to defend their work; but their responses have been weak at best, evasive at worst. Notably, they continue to write in a way that suggests, without stating outright, that debt at 90 percent of GDP is some kind of threshold at which bad things happen. In reality, even if one ignores the issue of causality—whether low growth causes high debt or the other way around—the apparent effects on growth of debt rising from, say, 85 to 95 percent of GDP are fairly small, and don’t justify the debt panic that has been such a powerful influence on policy.

At this point, then, austerity economics is in a very bad way. Its predictions have proved utterly wrong; its founding academic documents haven’t just lost their canonized status, they’ve become the objects of much ridicule. But as I’ve pointed out, none of this (except that Excel error) should have come as a surprise: basic macroeconomics should have told everyone to expect what did, in fact, happen, and the papers that have now fallen into disrepute were obviously flawed from the start.

This raises the obvious question: Why did austerity economics get such a powerful grip on elite opinion in the first place?

When applied to macroeconomics, this urge to find moral meaning creates in all of us a predisposition toward believing stories that attribute the pain of a slump to the excesses of the boom that precedes it—and, perhaps, also makes it natural to see the pain as necessary, part of an inevitable cleansing process. When Andrew Mellon told Herbert Hoover to let the Depression run its course, so as to “purge the rottenness” from the system, he was offering advice that, however bad it was as economics, resonated psychologically with many people (and still does).

By contrast, Keynesian economics rests fundamentally on the proposition that macroeconomics isn’t a morality play—that depressions are essentially a technical malfunction. As the Great Depression deepened, Keynes famously declared that “we have magneto trouble”—i.e., the economy’s troubles were like those of a car with a small but critical problem in its electrical system, and the job of the economist is to figure out how to repair that technical problem. Keynes’s masterwork, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, is noteworthy—and revolutionary—for saying almost nothing about what happens in economic booms. Pre-Keynesian business cycle theorists loved to dwell on the lurid excesses that take place in good times, while having relatively little to say about exactly why these give rise to bad times or what you should do when they do. Keynes reversed this priority; almost all his focus was on how economies stay depressed, and what can be done to make them less depressed.

I’d argue that Keynes was overwhelmingly right in his approach, but there’s no question that it’s an approach many people find deeply unsatisfying as an emotional matter. And so we shouldn’t find it surprising that many popular interpretations of our current troubles return, whether the authors know it or not, to the instinctive, pre-Keynesian style of dwelling on the excesses of the boom rather than on the failures of the slump.

David Stockman’s The Great Deformation should be seen in this light. It’s an immensely long rant against excesses of various kinds, all of which, in Stockman’s vision, have culminated in our present crisis. History, to Stockman’s eyes, is a series of “sprees”: a “spree of unsustainable borrowing,” a “spree of interest rate repression,” a “spree of destructive financial engineering,” and, again and again, a “money-printing spree.” For in Stockman’s world, all economic evil stems from the original sin of leaving the gold standard. Any prosperity we may have thought we had since 1971, when Nixon abandoned the last link to gold, or maybe even since 1933, when FDR took us off gold for the first time, was an illusion doomed to end in tears. And of course, any policies aimed at alleviating the current slump will just make things worse.

In itself, Stockman’s book isn’t important. Aside from a few swipes at Republicans, it consists basically of standard goldbug bombast. But the attention the book has garnered, the ways it has struck a chord with many people, including even some liberals, suggest just how strong remains the urge to see economics as a morality play, three generations after Keynes tried to show us that it is nothing of the kind.

And powerful officials are by no means immune to that urge. In The Alchemists, Neil Irwin analyzes the motives of Jean-Claude Trichet, the president of the European Central Bank, in advocating harsh austerity policies:

So is the austerian impulse all a matter of psychology? No, there’s also a fair bit of self-interest involved. As many observers have noted, the turn away from fiscal and monetary stimulus can be interpreted, if you like, as giving creditors priority over workers. Inflation and low interest rates are bad for creditors even if they promote job creation; slashing government deficits in the face of mass unemployment may deepen a depression, but it increases the certainty of bondholders that they’ll be repaid in full. I don’t think someone like Trichet was consciously, cynically serving class interests at the expense of overall welfare; but it certainly didn’t hurt that his sense of economic morality dovetailed so perfectly with the priorities of creditors.

It’s also worth noting that while economic policy since the financial crisis looks like a dismal failure by most measures, it hasn’t been so bad for the wealthy. Profits have recovered strongly even as unprecedented long-term unemployment persists; stock indices on both sides of the Atlantic have rebounded to pre-crisis highs even as median income languishes. It might be too much to say that those in the top 1 percent actually benefit from a continuing depression, but they certainly aren’t feeling much pain, and that probably has something to do with policymakers’ willingness to stay the austerity course.

Four years ago, the mystery was how such a terrible financial crisis could have taken place, with so little forewarning. The harsh lessons we had to learn involved the fragility of modern finance, the folly of trusting banks to regulate themselves, and the dangers of assuming that fancy financial arrangements have eliminated or even reduced the age-old problems of risk.

I would argue, however—self-serving as it may sound (I warned about the housing bubble, but had no inkling of how widespread a collapse would follow when it burst)—that the failure to anticipate the crisis was a relatively minor sin. Economies are complicated, ever-changing entities; it was understandable that few economists realized the extent to which short-term lending and securitization of assets such as subprime mortgages had recreated the old risks that deposit insurance and bank regulation were created to control.